AWE Management’s plan for their holdings of nuclear waste was developed during 2012 and 2013 as a ‘do minimum’ option to compare against other proposed courses of action. The plan involves sending 5,000 205 litre drums of Intermediate Level Waste (ILW) by road and rail to the Waste Treatment Centre at Sellafield, Cumbria. According to a document recently released through an FOI request, the majority of AWE’s waste holdings will remain on site and untreated until a second generation waste treatment facility at Sellafield is operational.

At the time the plan was developed AWE was under a regulatory requirement by the ONR (Office for Nuclear Regulation) to compress 1,000 drums of Higher Activity Waste (HAW) and repackage them in more modern containers by 2014. In 2011 the MoD had refused to allow more money to be spent on a plan to satisfy the requirement, after seismic concerns meant that retrofitting an existing building was not possible and a purpose-built facility would be needed instead, significantly increasing the cost. The waste is currently kept in a store at Aldermaston which is not large enough to accommodate waste expected from future operations, and many of the drums are older than their original design life.

Nuclear waste is classified into three main categories, according to its radioactivity and the attendant risks: High Level Waste (HLW), Intermediate Level Waste (ILW) and Low Level Waste (LLW). HAW is a classification which includes HLW and ILW and some types of LLW which are not accepted by the LLW Repository at Drigg in Cumbria. AWE’s waste holdings are not believed to include any HLW, and most of their LLW holdings have already been separated and sent to Drigg.

Prior to 2011, AWE had planned to build a supercompactor facility at Aldermaston, and had even purchased a supercompactor, which later was sold to the Nuclear Decommissioning Authority for use at Dounreay. Supercompaction involves a heavy-duty hydraulic press, which can compress radioactive waste drums into a flattened ‘puck’, several of which can then be immobilised in a cement-like material in a new waste container. Radioactive particles and liquid released during the process can be captured and processed in the same way.

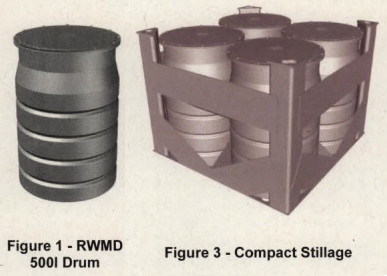

The first generation Waste Treatment Centre at Sellafield (known as WTC1), where the 5,000 drums are planned to be sent, is a supercompaction facility. NIS understands that the waste will be transported by road to a secure rail depot, possibly MoD Kineton in Warwickshire, where it can be loaded onto trains for transport to Sellafield. The waste processed at WTC1 will be stored in 500 litre drums which meet the criteria for the planned Geological Disposal Facility (GDF), an underground facility which the government intends to build as the permanent destination for the UK’s most radioactive waste holdings. At present no site for the GDF has been identified. After a number of unsuccessful attempts to select a site over several decades, the government published a policy framework for identifying a site in December 2018.

The processed waste is planned to be returned to AWE for storage until it can be sent to a GDF, and a new 2,200 square metre storage facility will be built on site to house it. When the plans were devised it was expected that AWE would be given a disposal slot at the GDF between 2070 and 2080, but due to the uncertainty around the GDF timetable AWE’s waste strategy envisages this ‘interim’ storage may be in use for 100 years or more.

The 5,000 drums that will be sent to WTC1 are the most hazardous amongst AWE’s waste holdings because they contain a higher quantity of fissile material. However, there are a large number of less hazardous 205 litre drums which would also have been processed if AWE had built an on-site supercompaction facility, but will now apparently remain untreated until at least the mid 2030s. The second generation Sellafield Waste Treatment Centre (WTC2) is not planned to be operational until 2036, and it is not clear what priority will be given to the wastes from AWE. The released documents concede that the plan involves moving away from an approach of treating waste holdings as soon as possible. The Office for Nuclear Regulation approved the current plan because processing the 5,000 more hazardous barrels could begin more quickly than the time it would take for an on-site supercompactor facility to be operational, particularly if there were delays in constructing the facility as there have been with other new facilities being built on the AWE sites.

The released document does not disclose the number of less-hazardous drums, but according to other documents in the public domain the number is around 14,500, of which 1,700 may be unsuitable for processing at WTC2.

All the waste plans considered by AWE involved a process of opening and sorting through some of the waste containers that they hold in order to ensure that as much of the waste as possible is in a form where it can be processed. This will be done with some of the unsuitable and unusual wastes, as well as some of the waste currently in containers that are larger than the 205 litre drums. These include wastes contaminated with oil and mercury, contaminated air filters, and waste that had been prepared for dumping at sea before the practice was halted due to public pressure in 1983.